Adobe

Walls: MATERIALS ENCYcLOPEDIA

Applications for this system

Load-bearing exterior walls

Infill walls

Interior walls

Interior decorative elements

Basic materials

Soils with fairly high clay content (25%–40%)

Straw or other natural fiber

Block forms (quick release preferable)

Mortar or slip

Insulation (where required)

Water-resistant finish (where required)

Control layers:

Water — The finished adobe block is typically the water control layer. It is possible to use vapor-permeable, water-resistant finishes on the surface or to include water-resistant additives to the earth mix before forming. It is also possible to use additional cladding over the adobe, but this is rarely done.

Air and Vapor — Solid and dense, adobe is an effective air control layer when laid in continuous, gap-free mortar or slip beds. The earthen walls are vapor-permeable.

Thermal — An adobe wall requires an additional thermal control layer in hot or cold climates (see Thermal Mass vs. Insulation sidebar). This layer can be on the interior, exterior of a single wall or center of a double wythe wall.

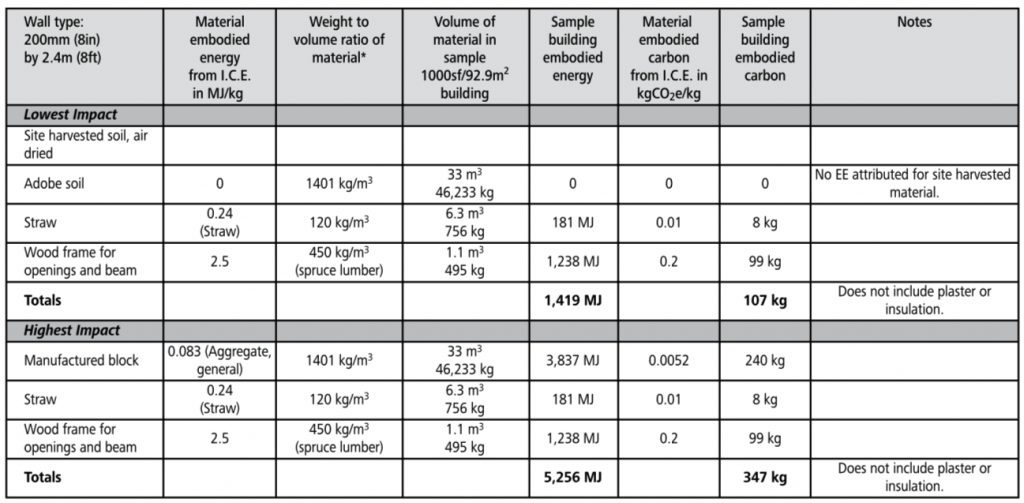

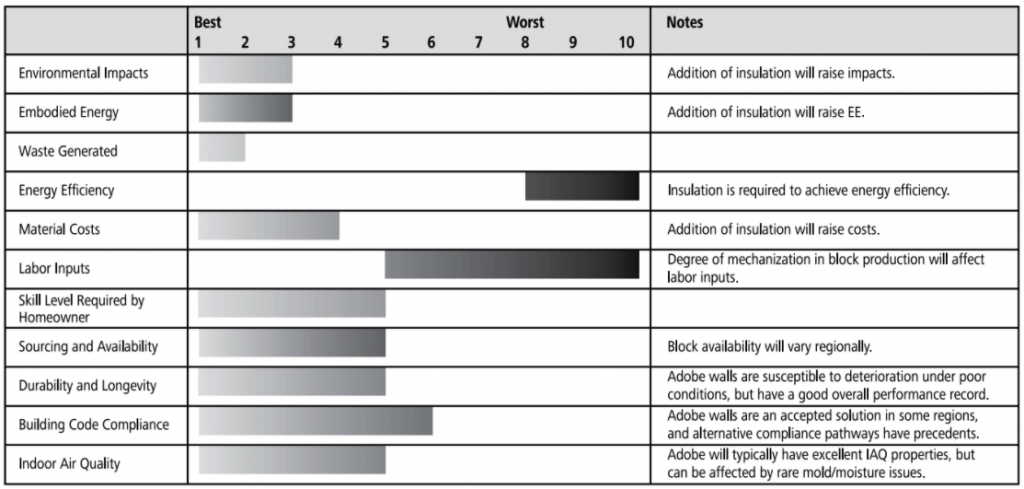

Ratings Chart for Adobe walls

The ratings chart shows comparative performance in each criteria category. Click on the tabs below for detailed analysis of each criteria.

- HOW THE SYSTEM WORKS

- ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS

- WASTE

- EMBODIED CARBON

- ENERGY EFFICIENCY

- MATERIAL COSTS

- LABOUR INPUT

- SKILL LEVEL REQUIRED

- SOURCING & AVAILABILITY

- DURABILITY

- CODE COMPLIANCE

- INDOOR AIR QUALITY

- RESOURCES

- FUTURE DEVELOPMENT

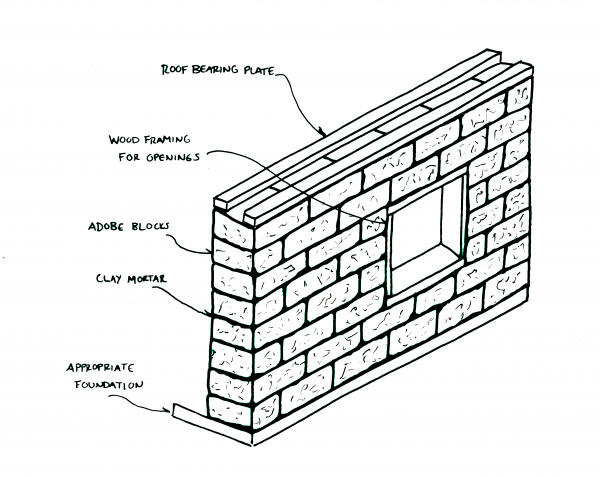

Adobe System

A soil with clay content of 25%–40% and a good distribution of sand and silt is moistened and thoroughly mixed with chopped straw or other natural fiber. The resulting mix is placed into block forms, released from the forms and allowed to fully dry.

Once dried, adobe blocks are laid up in a running bond similar to other masonry techniques. Mortars can be clay based, rather than using more conventional lime or cement mixes. Conventional mortaring techniques are used with joints ranging from ¼”–¾” (6–20 mm).

All of the conventions of block and bricklaying apply to building with adobe block. Window and door openings use wooden, concrete or steel lintels. At the top of the wall, a wooden, concrete or steel beam system is used to provide rigidity and a fastening point for the roof.

Adobe walls require insulation in many climates. Insulation can be applied on the interior or exterior wall, or a double wythe system can be insulated in the core.

Recently, some have experimented with “pour-in-place” systems where block forms are placed where needed on the wall, filled and the forms removed immediately. With a stiff mix, this can work well and reduce waiting time and block handling, as well as eliminating the need for mortaring dry blocks together. In this way, the system becomes a hybrid between adobe and cob.

Environmental Impact Rating

Harvesting — Negligible to Low

Site soils will have negligible impacts. Regionally sourced soil will have minimal impacts from the machinery used for excavation and handling.

Manufacturing — Negligible to Low

Human-powered processes will have negligible impacts. Mechanical mixers will have low impacts from the fossil fuel use of the machinery.

Transportation — Negligible to Moderate

Sample building uses 46,233 kg of adobe soil:

43.5 MJ per km by 35 ton truck

Adobe blocks are typically made on the construction site. As a heavy material, impacts accrue proportional to distance traveled if blocks are made off-site.

Installation — Negligible

Waste: Negligible

Biodegradable/Compostable — All unmodified soil and straw, block offcuts.

Chart of Embodied energy & carbon

Energy Efficiency: Low

An adobe wall has a lot of thermal mass and can easily be an airtight wall system, but it has no inherent insulation value (see Thermal Mass vs. Insulation sidebar). The overall energy efficiency of an adobe wall system will depend on the insulation strategy. Insulation can be placed on either the interior or exterior of the wall or a double wythe system can have insulation in the middle of the wall.

Insulation on either side of the wall will force a builder to create a finished surface over the insulation, which adds cost and complexity to the wall system and isolates all of the available thermal mass on one side or the other. Core insulation is more effective and leaves the blocks exposed as the finish on both sides. Unlike rammed earth walls, core insulation can be added after the walls are built, leaving many more options for the builder, including loose-fill insulation types poured between the wythes.

Material costs: Low to moderate

Labour Input: moderate to High

There are two stages to the creation of most adobe wall systems. The manufacture of the blocks requires labor to create the forms, make mix, place it in forms and release. The process of mortaring up the blocks requires mixing mortar, moving blocks and placing them on the wall.

The pour-in-place system reduces some of this labor and makes the process a single stage.

Skill level required for homeowners: Easy to moderate

Newcomers can undertake the production of blocks with a bit of training or experience in mixing and pouring adobe. The block laying process using clay mortars is much more forgiving than using conventional cement-based mortars and can also be done by those with little previous experience, as long as the basic premises of masonry construction are followed.

Sourcing & availability: Easy to moderate

In some regions, especially in the American Southwest, demand for adobe bricks is such that there are commercial production facilities and blocks may be purchased ready-made. However, in most parts of North America, adobe is a site-made material and will not be able to be sourced as a building product.

Durability: moderate to High

Adobe is a material with a long, proven history. It shares with other earthen building techniques vulnerability to deterioration due to exposure to water. But when kept relatively dry by the use of generous roof overhangs, good foundations and smart building details, adobe buildings can last for centuries. Adobe walls are straightforward to repair by applying more wet mix to any worn or problematic areas.

Plasters and other protective sidings can reduce the potential for damage from precipitation.

Code compliance

There is acceptance of adobe construction in some codes, including some prescriptive standards used regionally. Sufficient testing of adobe walls exists to inform the design of a wall system by a structural engineer where codes are not in place.

Indoor air quality: moderate to high

Uncontaminated earth is generally agreed to have no inherently dangerous elements and is consistent with the aims of high indoor air quality.

Soil contamination, from natural sources like radon or synthetic sources like petrochemicals, is possible, and it is wise to inspect and/or test soils carefully before using them to build a house.

Resources for further research

Schroder, Lisa, and Vince Ogletree. Adobe Homes for All Climates: Simple, Affordable, and Earthquake-Resistant Natural Building Techniques. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2010. Print.

McHenry, Paul Graham. Adobe and Rammed Earth Buildings: Design and Construction. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona, 1989. Print.

Byrne, Michael, Dottie Larson, and Amy Haskell. New Adobe Home. Layton, UT: Gibbs Smith, 2009. Print.

McHenry, Paul Graham, Jr. Adobe: Build It Yourself, 2nd Revised Edition. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona, 1985. Print.

Sanchez, Laura, and Al Sanchez. Adobe Houses for Today: Flexible Plans for Your Adobe Home. Santa Fe, NM: Sunstone, 2001. Print.

Van Hall, Michael. The Cheap-Ass Curmudgeon’s Guide to Dirt: Hand Building with Adobe, Papercrete, Paper-Adobe and More. Tucson, AZ: Cheap-Ass, 2009. Print.

Future development

Adobe block construction has a long history and the building method is basic and well understood, so the technique and materials are unlikely to change significantly. Mixing equipment and mechanized production already exist and are in use in some areas, and it is likely that this will spread as interest in affordable, low-impact construction grows. High transportation costs for heavy materials create conditions for regionalized production, rather than large, central factories. The long drying times for adobe blocks mean that production requires climates with warm temperatures and infrequent rain. Creating large, indoor facilities and/or the use of fossil fuels to create ideal drying conditions would add cost and complexity to an otherwise simple process. However, costs would be much lower than for fired brick, so it is feasible that production facilities could develop in areas outside historic adobe regions.

Tips for a successful adobe wall

1. The construction of good block forms is important for adobe walls. Filling and releasing forms is done repeatedly while making adobe blocks, and a streamlined process using forms that allows quick release of material will increase productivity.

2. Soil with too much clay can be amended with additional sand and soils that are naturally too sandy can have bagged clay or imported clay soils added. Because adobe mixtures are feasible with a wide range of clay/sand/silt ratios, there is usually a way to make local soils work.

3. Create a mixing system that is appropriate to the size of the walls being built. For larger projects or those with time restraints, a more mechanized system will be useful. Check resources for tips on mixing in a variety of ways including animals, mortar mixers, tractors and backhoes.

4. Adobe walls can take a long time to build and then a long time to dry out thoroughly. Projects in cold climates or climates with a long rainy season need to be timed to leave adequate drying time before completion of finishes and occupancy.