Lime Finish Plaster

Finishes: MATERIALS ENCYcLOPEDIA

Applications for this system

Finish coat for application over most interior substrates, including plaster, drywall, magnesium oxide board, brick and sheet wood materials

Finish coat for application over plaster or masonry exterior substrates

Basic materials

Hydrated lime (for air-curing lime plaster)

Hydraulic lime (for hydraulic-curing lime plaster)

Pozzolanic material (if required to create hydraulic curing of hydrated lime, including fired clay, gypsum, slag, fly ash)

Sand

Fibers (if required)

Pigments (if required)

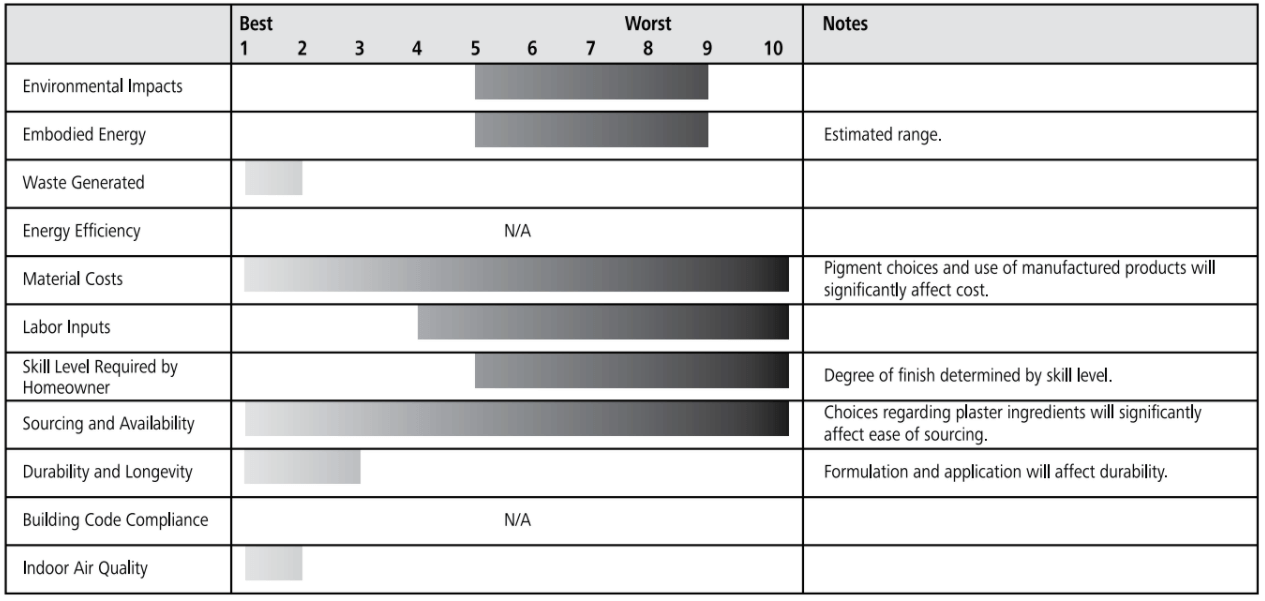

Ratings Chart for Lime finish plaster

The ratings chart shows comparative performance in each criteria category. Click on the tabs below for detailed analysis of each criteria.

- HOW THE SYSTEM WORKS

- ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS

- WASTE

- MATERIAL COSTS

- LABOUR INPUT

- SKILL LEVEL REQUIRED

- SOURCING & AVAILABILITY

- DURABILITY

- INDOOR AIR QUALITY

- RESOURCES

- FUTURE DEVELOPMENT

Lime finish plaster System

Lime finish plasters have a long history, with centuries of development and artistry resulting in a range of recipes and application techniques.

Lime finish plasters can be made with either hydrated lime or hydraulic lime (see previous chapter) and finely graded aggregate to allow for a very thin skim coat.

For application over smooth substrates, an adhesion coat is used to help the plaster to bond to flat surfaces. This coat is typically a mixture of sand and glue (natural flour paste or casein glue) that is brushed or rolled onto the wall, creating a textured surface.

Many different finishing techniques are used on lime finish plasters, from a highly polished surface (marmorino and tadelakt, see sidebar) to a rough trowel or skip trowel look.

Environmental Impact Rating

Harvesting — Moderate

Limestone is a non-renewable but abundantly available material. It is mechanically extracted from quarries. Impacts can include habitat destruction, surface and ground water interference and contamination.

Manufacturing — High

Limestone is mechanically crushed and heated (900–1100 ∞C / 1650–2000 ∞F for lime and 1400–1600 ∞C / 2500–2900 ∞F for cement). This is an energy-intensive process during which large amounts of fossil fuels are burned, contributing to habitat destruction and air and water pollution and carbon emissions. During the kilning process, large amounts of CO2 are emitted (approximately 1 kg of CO2 for every 1 kg of lime or cement). In the case of lime, it is slowly recombined with the lime through the carbonization process. Thin finish coats of lime plaster are likely to reabsorb the majority of the CO2 as the surface area to thickness ratio is quite high.

Sand is mechanically extracted from quarries and mechanically crushed. Impacts can include habitat destruction and surface and ground water contamination.

Transportation — Moderate to High

Limestone is available in many regions, but is not necessarily harvested and processed in all regions. Impacts for this heavy material will vary depending on distance from the site. Natural hydraulic lime (NHL) most commonly comes from France or Portugal, carrying high transportation impacts for use in North America.

Sand is locally harvested in nearly every region, and should have minimal transportation impacts.

Installation — Negligible

Waste: Negligible

Compostable — Lime plaster can be left in the environment or crushed to make aggregate. Hydrated lime plaster can be kept wet indefinitely and doesn’t need to be disposed. Quantities should be low, as it is mixed in small batches.

Landfill — Packaging (usually paper and/or plastic bags) from lime. Quantities depend on the size of the job.

Material costs: moderate to high

The basic ingredients for lime plaster are moderately priced, but pigments can add significantly to costs. Manufactured products are more costly than home made versions.

Labour Input: moderate to High

Lime plaster requires significant labor input. Substrate preparation, mixing and application are all labor-intensive processes. Single-coat applications will typically require less labor time than multiple coats.

Health Warning

Lime and sand are high in silica content and are dangerous to inhale. Lime is caustic when wet and can cause irritation of the skin that ranges from mildly uncomfortable to painful chemical burns.

Skill level required for homeowners

Preparation of substrate — Moderate

On smooth surfaces, an adherence coat will need to be painted or rolled. Accurate masking of all intersections is an important step with a strong influence on the final appearance.

Application of Finish — Moderate to Difficult

The basics of trowel application of finish coat plaster require some practice. Quality of finish will improve dramatically with experience. High-gloss finishes like marmorino or tadeltakt (see sidebar) can require a fair bit of practice.

Sourcing & availability: Easy to Difficult

The materials to mix lime finish plaster are widely available from masonry supply outlets. Prepared mixes, especially those intended to create a particular kind of finish, are commercially available but may require sourcing from manufacturers or specialty plaster distributors.

Durability: High

All forms of lime plaster can have a long lifespan of at least a hundred years, and potentially longer. Proper maintenance will have a lot of impact on durability. Repair of cracks and reapplication of protective coatings (where required) will help to maximize lifespan.

Indoor air quality: high

Lime finish plaster should have no negative impact on IAQ. The antiseptic nature of lime can discourage mold growth, helping to maintain good IAQ in damp areas.

The dust from mixing lime plaster and from cleanup after plastering is high in silica content and can be pervasive. Be sure to protect air ducts and other vulnerable areas during plastering and clean up to avoid contamination.

Resources for further research

Guelberth, Cedar Rose, and Daniel D. Chiras. The Natural Plaster Book: Earth, Lime and Gypsum Plasters for Natural Homes. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society, 2003. Print.

Weismann, Adam, and Katy Bryce. Using Natural Finishes: Lime- and Earth-Based Plasters, Renders and Paints: A Step-by-Step Guide. Totnes, UK: Green, 2008. Print.

Future development

The practice of harvesting and manufacturing lime plaster is thousands of years old. Modern practices are efficient and the results very consistent compared to historical ones. It is unlikely that developments in the production of lime will change much, though greater efficiency in kilns and use of waste heat may reduce embodied energy as fuel costs rise.

Lime plastering may grow in popularity as the understanding of vapor-permeable wall systems increases, but it is unlikely that lime plaster will return to its once dominant place as a very common and an artisanal finish.

Tips for successful Lime finish plaster

1. If plastering over smooth, unplastered substrates, an adherence coat of glue and sand is required.

2. A good plastering job requires properly placed plaster stops or transition considerations at every junction. Careful masking of all edges will produce a professional appearance. Pull tape before plaster hardens to avoid uneven edges.

3. Lime plaster requires attention during the curing process. In particular, it is important with all lime-based plasters to maintain an adequate level of moisture in the curing plaster. Direct exposure to sunlight or wind can rob the plaster of moisture very quickly, resulting in poor curing and cracking. The plaster will also need regular misting for a few days to keep it properly hydrated.

4. Lime plasters can develop a “cold edge” while being applied. These seams will be apparent in the finished appearance, so be sure to start and finish sections of wall that can be completed in one application.

5. There are many excellent resources to aid with the successful mixing and application of lime plaster. Be sure to research thoroughly before application.