There is a remarkable paradox when it comes to introducing new technologies, in construction or any other field. We expect new ideas or technologies to live up to unrealistically high standards, while at the same time we accept as normal many existing ideas or technologies that are inherently, deeply flawed.

It is a commendable tendency to try and be “objective” about new ideas and weigh as much evidence as we have at hand in deciding whether or not we think they are worthy. But we tend to be much less than objective about the ideas and technologies we use on a daily basis. Because they are normal to us, we rarely examine them in any meaningful way. A certain degree of inevitability is attributed to the ideas we’ve normalized; we don’t see them as choices in the same way we see new ideas as choices.

There are countless examples of this paradox in everything we do. In the building world, we find a great example in the use of milled lumber as our prime residential building material. Wood has every flaw imaginable for a building material. It burns; it rots; it’s insect food; it warps, twists and cracks; it’s a great medium for growing mold; its structural properties vary greatly by species, milling, drying and storing practices; it’s often grown far from where it’s needed; it’s heavy; it’s dimensionally unstable as climatic conditions change…. In fact, if an attempt were made to introduce wood as a building material in today’s building code climate, there is little chance that it would ever be approved!

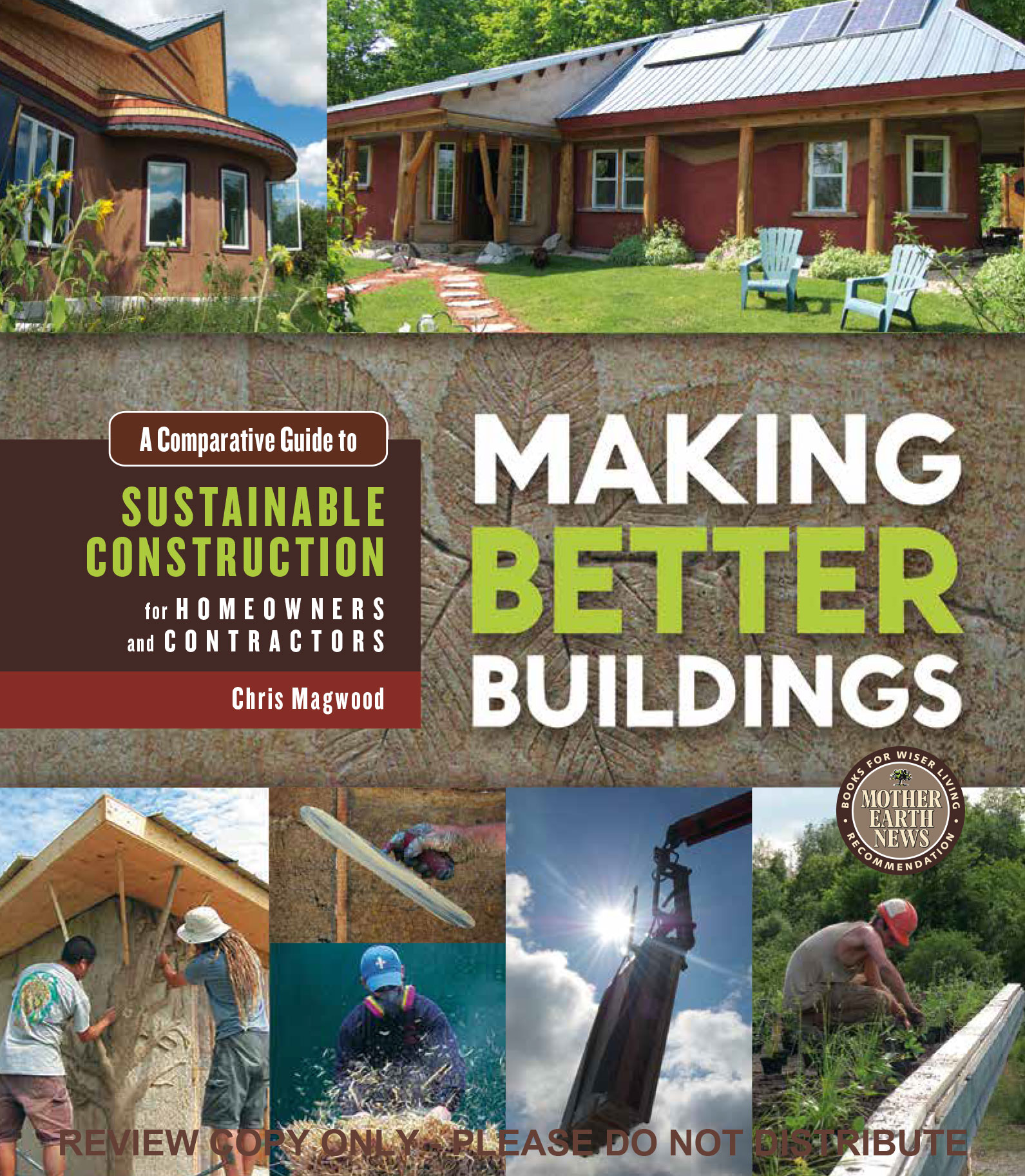

And yet milled lumber has come to serve us very well as a building material. Collectively we used a natural material that was available to us and figured out how to deal with all its “micro-flaws.” In the end, we’ve normalized it and built an entire successful industry around an entirely flawed material! But if we introduce a new material that has even a small number of the flaws inherent in wood, we find ourselves up against naysayers who can only see the flaws and not the possibilities for being able to work with them. Straw bale and earthen building techniques can have many fewer flaws than wood construction, and yet are subjected to much more scrutiny.

There is no such thing as an idea or technology with no flaws. Recognizing this simple point is key to being able to consider new ideas fairly. There is an experiment I perform at public talks: I ask the audience how many of them have had to deal with a toilet backup at some point in their lives. The show of hands is almost guaranteed to be unanimous. Then I ask that same audience if they think the flush toilet is a bad, flawed idea that ”doesn’t work”; very few say Yes. And this despite having to regularly deal with some very unpleasant consequences due to an inherent flaw in the technology! We accept the micro-flaw of an occasional toilet backup as a reasonable trade-off for the convenience of using a flush toilet. However, I hear frequently that composting toilets “don’t work” based on second-hand reports of a single incidence of the composter smelling or not composting properly. There’s the paradox: the “normal” technology fails disgustingly at a rate of almost 100 percent, and yet the “alternative” is the one that gets branded as something that “doesn’t work.” In truth, both systems have some inherent flaws, and both will fail on occasion. We’ve just learned to accept the micro-flaws of one and reject the micro-flaws of the other.

Every new material has a number of micro-flaws, as do those conventional technologies they might replace. One should not attempt to gloss over any micro-flaws, as you will be living with them for a long time. But the comparisons between sustainable technologies and their conventional counterparts do not and cannot stop at the level of micro-flaws. Sustainable building strives to address the larger and much more important macro-flaws in our approach to building.

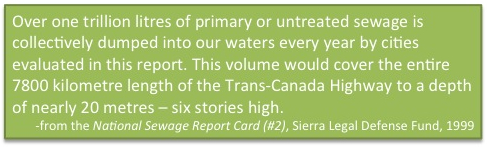

It is at the macro level that all of the materials in this book have their advantages over conventional practices. To continue the comparison between flush toilets and composting toilets, we can see that both can be practically functional but also have some micro-flaws. On the macro level, however, the flush toilet is part of a system that sees billions of gallons of untreated or partially treated sewage enter our streams, rivers, lakes and oceans, while using vast amounts of clean potable water and a very expensive public infrastructure. Meanwhile, composting toilets can turn human “waste” into a valuable fertilizer with minimal infrastructure and little to no fresh water usage. It is at this macro level that we should be assessing our building technologies. In this case, the advantages of the composting toilet should be very clear.

If we can start making wise choices at the macro level, we can trust ourselves to figure out how to minimize the micro-flaws of any technology. We humans are incredibly good at refining ideas and techniques. Through repetition, we gain insights that allow us to make the process better and better each time we use it. We’re good at doing things better, but we’re not very good at doing better things. Doing better things means looking beyond the micro-flaws and basing our choices on minimizing impacts at the macro level.

One of the challenges in adopting any new technology is figuring out where we are on the learning curve, and at what point on that curve we feel comfortable jumping on board. Some of the systems we work with in sustainable building are quite well developed, with installation and maintenance instructions that are very complete and manufacturer and installer warranties that back them up. Others are relative newcomers (at least in the modern context) and the instruction manuals are literally being written and refined right now. We may not know the very best way to use some of these systems until a lot more early adopters have trial-and-errored their way to some kind of standardized practice. There are rewards to helping break new technologies, and also risks.

Figuring out what choices to make in a sustainable building project can be overwhelming. It requires a lot of level headed research, a willingness to question 2G2BT (too good to be true), and a clear understanding of your goals and your budget. Endeavour’s Design Your Own Sustainable Home workshop is a great way to start sorting out all these choices for yourself!

(This blog is adapted from the book Making Better Buildings: A Comparative Guide to Sustainable Construction)