The Green Glut

The past 10 years have seen an explosion of building products being marketed to designers and builders as “green.” As the immense impacts buildings have on our planet’s ecosystem started to become clear to the mainstream building industry, marketing departments went crazy to identify just about every kind of product as being “green” in some way or another.

From my position as someone advising people on green building options, this “glut of green” causes a lot of confusion. If every product is sold as green, what does it mean to really be green?

Real Green Criteria

In order for a product to meet Endeavour’s standard for green, it has to meet several criteria:

- Must have low ecosystem impacts in the harvesting and production of the product. This includes considering both how and where the raw materials are extracted and handled, and what kinds of pollution/emissions happen during the production processes.

- Must have low embodied energy and carbon footprint. This means understanding how much (and what kind) of energy is used to harvest and process the product and the size of the fuel and carbon footprint.

- If applicable, the product must positively impact the long-term energy efficiency and/or performance of the building.

- Should not use and definitely must not emit any dangerous chemicals or off gassing, during manufacturing, use in the home, or at end-of-life.

- Must be durable, and have a reasonable end-of-life strategy (ie, where does it go when it’s taken out of the building).

- Upcycled, recycled and re-purposed materials are preferable.

- Local production is preferable to long-distance shipping.

Meeting Just One Criteria = Not Good Enough

Many building products are sold as “green” if they meet any one of those criteria. Unfortunately, the majority of building products sold as “green” fail (often miserably) when examined against all of these criteria. While the sales team will glowing focus on any glimmering of green in one category, rarely does anything with the green label come close to satisfying a full range of ecological criteria.

A Materials Revolution?

The dichotomy between products posing as green and those that are truly green was on display at the recent Living Products Expo, which I attended in Pittsburgh last week. Organized by the International Living Future Institute, the event was billed as “Inspiring a Materials Revolution.” And kudos to the organizers, because this really was the intention of the event.

What Makes Foam Green?

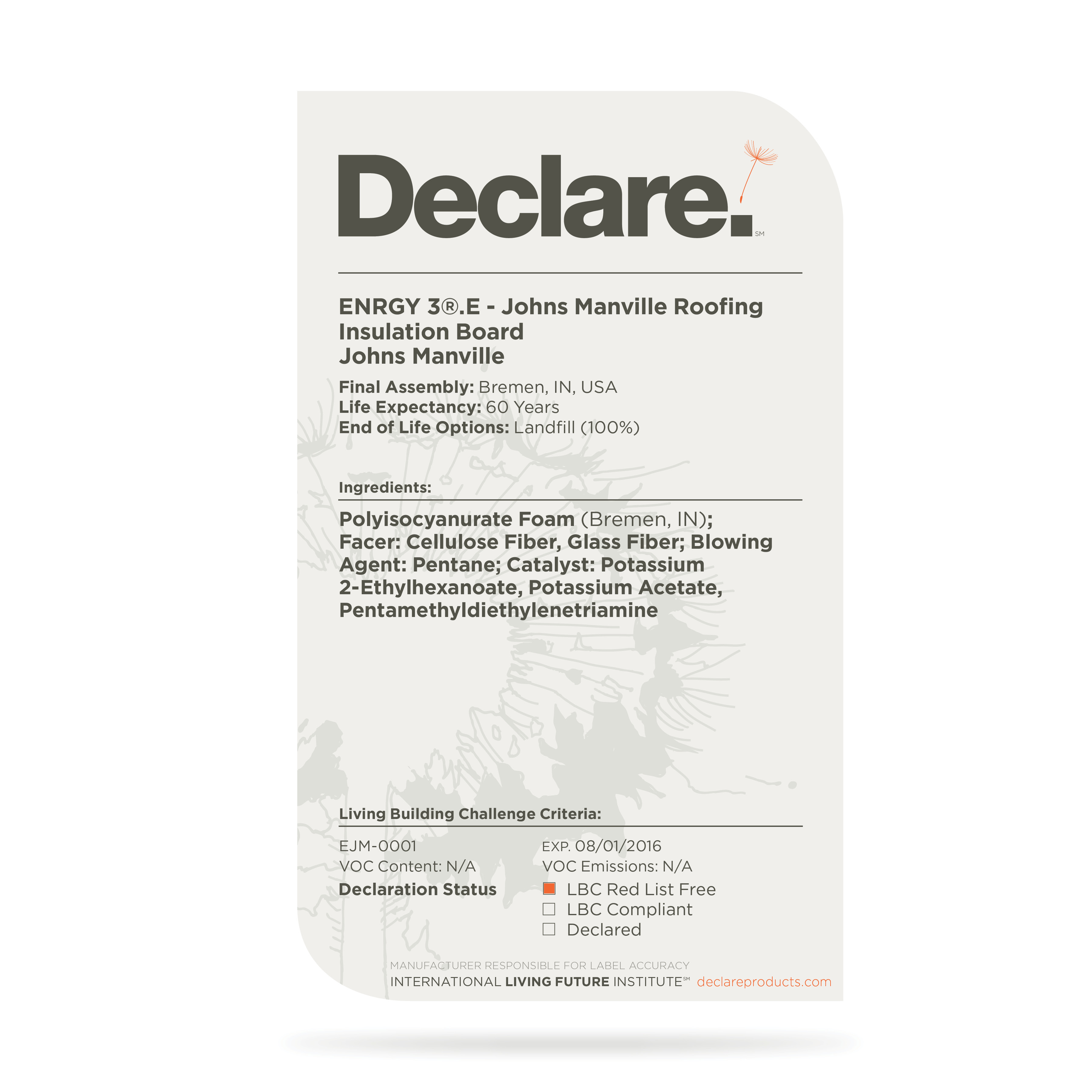

But at one point I found myself in a session that featured several product manufacturers presenting on their new green products. One was a rep from Johns Manville presenting a new polyisocyanurate foam insulation product that does not have added fire retardants (called Energy 3.E). Now this is an interesting achievement, since the flame retardants used in foam insulation are among some of the worst and most persistent chemicals in use on the planet, and up to 15-20% of flame retardant by weight is used in foams. The San Antonio Statement on Brominated and Chlorinated Flame Retardants should be enough to scare all of us away from using any products that use these flame retardants, so to have a foam insulation that eliminates them from its chemistry (without using questionable substitution) can be viewed as a major step, one worthy of the label “green.”

Except that if we put even this insulation to the test of our criteria list, it still fails on many counts. The foam is still a petro-chemical product, and if we don’t like what the oil industry does to the planet (from exploration impacts to drilling sea beds or excavating tar sands to the vast amounts of energy consumed and carbon produced to spills and “toxic events”) then it’s hard to see any foam product as being green. Foam insulation has very high embodied energy and carbon output. It still uses questionable chemistry, has no end-of-life plan and is shipped long distances from a centralized factory. Energy 3.E might be “greener” than other foams, but I don’t think it can really be called green or sustainable. This despite the fact that the product has won all kinds of green awards and has been widely celebrated.

Real Green Insulation

Real Green Insulation

This point was driven home by the next presenter at the same session, this time from Ecovative Design. This company has developed “mushroom foam,” a material that is made from mycelium (mushroom roots) grown amongst agricultural waste fibers. Among its many uses, it can be made into an insulation product with very similar performance qualities as plastic foam. This material satisfies all of the stringent criteria we apply to products in our buildings, and it is naturally flame resistant (interestingly, it turns out that the phosphorus atom the Johns Manville scientists managed to insert into their foam occurs naturally in the mycelium). Unfortunately, Ecovative’s insulation products have not yet reached the mass market, while the foam product has. But the stark difference between the two is a perfect illustration of the difference between being “sort of green” and “really green.”

At the same conference, I gained a more in-depth understanding of two programs that are intended to help builders tell the difference between real green products and those that are just pretending to be green. Which you will read shortly why this was so important. The timing couldn’t have been better.

Cradle to Cradle Certification

Cradle to Cradle Certification

The Cradle to Cradle Products Innovation Institute certifies products on a scale from “bronze” to “gold” based on their satisfaction of a wide-ranging set of criteria. The C2C Products Registry allows one to select a product category (such as Building Supply and Materials) and find products that have met their very high standards. I highly recommend this when searching for truly green products to use in buildings, though the overall number of products is still relatively small. There were so many things that I learned about what is truly considered green. I was under the impression that there were more products that are actually green. Now that I have been educated I am prepared to go help a family member who is dead set on redoing a set of buildings he owns in the austin industrial district.

The Declare Label

The Declare Label

Declare is a labelling system introduced by the Int’l Living Future Institute. The Declare label is billed as “a nutrition label for the building industry.” It focuses largely on a transparent declaration of all the ingredients in a product, and where those individual components come from. The Living Building Challenge building certification program has a “red list” of chemicals that it does not allow to be in a building. This label is a means of finding out if a product contains a red list chemical, and what things it contains that may not be desirable even if it is not on the red list. Declare does not consider ecosystem impacts, carbon emissions or other elements of manufacturing, and so is not quite as comprehensive as Cradle To Cradle, but it is still a great development and a useful tool for builders looking at green in a deeper way.

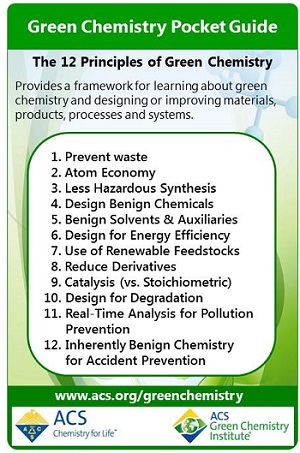

Green Chemistry and Local & Natural

As stated in the Living Product Expo’s desire to spark a “materials revolution,” there is a real move happening toward creating and using building systems that are truly better for the planet. John Warner, a founder of the “green chemistry movement” was a speaker at the Expo, and more and more material developers are starting to use the principles of green chemistry for the built environment. Having presented to the Expo about Endeavour’s methods for prefabricating straw bale wall panels, I found it interesting that the most promising sustainable building systems are relatively low-tech, use waste streams from other processes and are simple to replicate in smaller, regional “micro-factories.” Mushroom foam, straw bale walls, cellulose insulation and so many other effective, truly green materials don’t require major industrial apparatus. To a large degree, this is what makes them truly green. Keeping it simple, local and natural is often the best way to ensure it’s green!

As stated in the Living Product Expo’s desire to spark a “materials revolution,” there is a real move happening toward creating and using building systems that are truly better for the planet. John Warner, a founder of the “green chemistry movement” was a speaker at the Expo, and more and more material developers are starting to use the principles of green chemistry for the built environment. Having presented to the Expo about Endeavour’s methods for prefabricating straw bale wall panels, I found it interesting that the most promising sustainable building systems are relatively low-tech, use waste streams from other processes and are simple to replicate in smaller, regional “micro-factories.” Mushroom foam, straw bale walls, cellulose insulation and so many other effective, truly green materials don’t require major industrial apparatus. To a large degree, this is what makes them truly green. Keeping it simple, local and natural is often the best way to ensure it’s green!